The family of a 12-year-old boy who died in South Carolina this month have confirmed his cause of death to be an infection associated with Naegleria fowleri, more commonly referred to as a “brain-eating amoeba.”

It’s believed the boy, identified as Jaysen Carr, contracted the infection while swimming in Lake Murray, a central South Carolina reservoir popular with swimmers, boaters and fishermen, according to the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.

“The family has many questions about how and why Jaysen died and wants to do everything in their power to ensure this doesn’t happen to another family,” an attorney for Carr’s family wrote in a statement shared with Nexstar’s WCBD.

What is Naegleria fowleri?

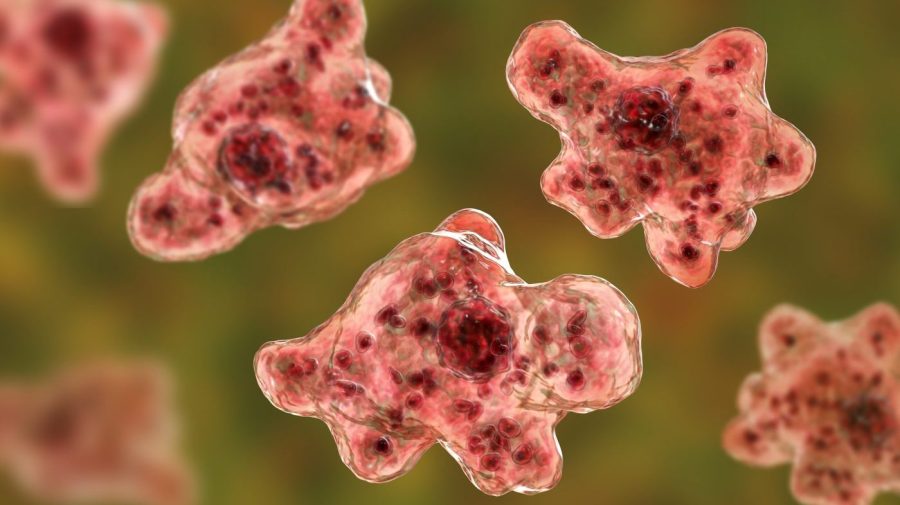

Naegleria fowleri is a single-celled organism primarily found in warm freshwater and soil, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“It’s very commonly found in nature, in soil or warm freshwater around the world … or in places where the water is warm for other reasons, like a thermal hot spring, or pool water that isn’t chlorinated properly,” Dr. Dennis Kyle, a professor of infectious diseases and cellular biology at the University of Georgia and the scholar chair of antiparasitic drug discovery with the Georgia Research Alliance, once explained in an interview with Nexstar.

The organisms have also been observed in improperly treated tap water, and, in lower concentrations, even cooler freshwaters.

The highest concentrations, though, are generally found in freshwater with surface temperature readings of 75 degrees F or higher, especially for extended periods of time.

How do infections occur?

Infection of N. fowleri usually occurs after water is forced into the nose, allowing the organism to enter the nasal cavity and cross the epithelial lining into the brain, where it begins destroying the tissue of the frontal lobe, Kyle said.

There’s an increased risk among those who partake in freshwater activities during the warmer months, he added.

“This time of year is when we typically hear about these cases,” Kyle said of the summertime, in general. “When people are out doing summer activities in the water, or on the lakes.”

The resulting brain infection, known as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), can lead to symptoms including fever, headaches, stiff neck, seizures and hallucinations within two weeks of exposure. It is almost always fatal, with death occurring “within about 5 days after symptoms first begin” but potentially up to a few weeks afterward, the CDC says.

Can it be treated?

Treatment of Naegleria fowleri infection consists of antifungal and antibiotic cocktails, and doctors have also induced hypothermia in patients to reduce fevers and protect undamaged brain tissue while the treatments are administered.

Survival, however, is “rare,” with a fatality rate estimated at about 97 percent the CDC says. Early detection and treatment can be key to improving chances, but infections may go ignored — or be misdiagnosed — until it’s too late.

Kyle, in a previous interview with Nexstar, said he was only aware of a handful of cases in which patients have survived, but he was optimistic about the use of collecting cerebral spinal fluid for testing purposes.

Prevention (e.g., avoiding warm freshwater bodies of water, wearing nose plugs, keeping your head above water, etc.) is currently the best way to combat infection. Raising awareness of the danger also helps, Kyle said.

“But I think any warm freshwater facility, or hot spring … and at splashpads, you have to look at it carefully,” he told Nexstar. “It’s incumbent on people running these facilities to minimize risk and minimize exposure.”

Who is most often infected?

Anyone can contract Naegleria fowleri infection, but the CDC has identified “young boys” as the group infected most often.

“The reasons for this aren’t clear. It’s possible that young boys are more likely to participate in activities like diving into the water and playing in the sediment at the bottom of lakes and rivers,” the agency said.

Is climate change making infections more common?

Even the CDC acknowledges that climate change may indeed be “a contributing factor” to the conditions which allow Naegleria fowleri to thrive.

“Warmer climates means, yes, more exposure and more cases,” Kyle had said, adding that there had been a “significant increase” in cases in recent years.

But he warned that increased cases cannot be linked solely to warmer waters, but rather more awareness and fewer misdiagnoses.

“There’s more recognition that these amoeba are possibly causing disease, when before, virologists were misclassifying these cases as bacterial meningitis or [other diseases],” he said.

WCBD’s Sophie Brams contributed to this article.