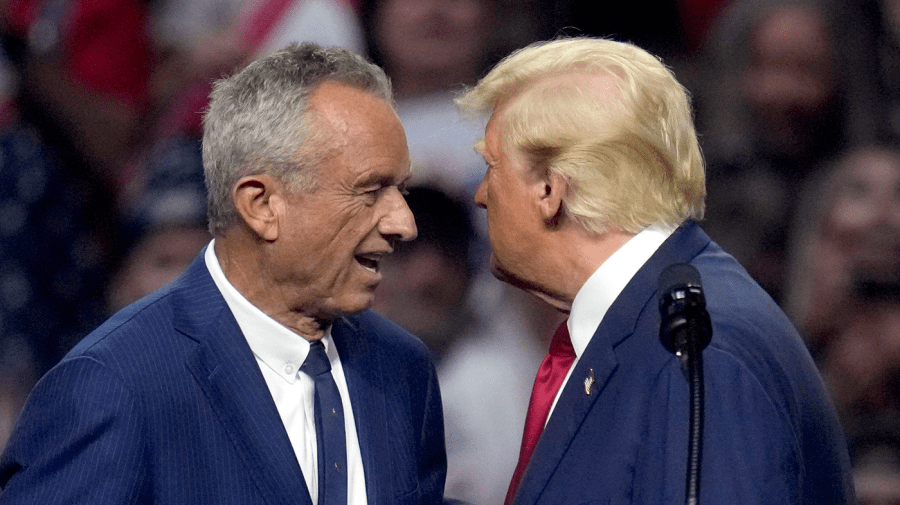

Health experts are worried about Robert F. Kennedy Jr. could influence former President Trump’s public health policies in a second term, after the prominent anti-vaccine advocate suspended his independent campaign for president and jumped aboard Trump’s.

Upon announcing the move last week, Kennedy said Trump had “asked to enlist me in his administration.” Kennedy’s former running mate, Nicole Shanahan, said earlier this month Kennedy would do an “incredible job” as secretary of health and human services.

While Trump has not committed to any specific role for Kennedy, he appointed his former opponent to his presidential transition team, and in a leaked phone call in July suggested Kennedy would have a “big” role in his administration.

Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr., told conservative radio host Glenn Beck this month he would support Kennedy taking over a government agency to “blow it up.”

And this is exactly what many health experts fear would happen to a public health agency — like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health — with Kennedy at the helm.

“From a health perspective this would be nothing short of chaos,” said Robert Murphy, a professor of infectious disease at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“He’s proven himself to be a dangerous fanatic who doesn’t have a science background and who doesn’t believe in science.”

“We’re in a lot of trouble if he has any role, any leadership position related to many things, but health in particular,” he added.

Murphy used Samoa’s deadly measles outbreak as an example of the harm Kennedy can cause. A wave of the virus infected more than 5,600 people on the tiny Pacific island nation in 2019, killing 83 people.

Many things contributed to the outbreak, including a drop in vaccination rates due to a public health scare the year before. In 2018, two babies in Samoa died shortly after receiving the MMR vaccine, causing vaccine hesitancy.

But the vaccine did not cause the infants’ deaths. The two nurses who administered the shots to the babies wrongly mixed the vaccines with a liquid muscle relaxant instead of water, causing them to stop breathing after being injected.

The deaths prompted the Samoan government to temporarily stop its vaccine program, which contributed to the fall in vaccination rates.

That same year, the Children’s Health Defense, a group long headed by Kennedy, questioned the safety of the vaccines given to the babies in several Facebook posts, according to The Washington Post, which noted the group never updated its posts to explain the nurses’ error.

During the 2019 outbreak, Kennedy publicly supported vaccination opponents on the island, including Australian Samoan anti-vaccine activist Taylor Winterstein. However, in the 2023 documentary “Shot in the Arm,” Kennedy said he had “nothing to do” with people not getting vaccinated in Samoa.

“I never told anybody not to vaccinate. I didn’t go there with any reason to do with that,” he said in the film.

Kennedy often gives mixed or contradictory messages on vaccines.

He has denied being against vaccines outright, but has long peddled debunked conspiracy theories about vaccines. At a congressional hearing last year he denied telling people to avoid getting vaccinated, but two years earlier said on a podcast that he regularly tells strangers not to vaccinate their babies. And on CNN in December he denied saying no vaccines are “safe and effective,” despite saying exactly that in an interview last July.

Health officials are already concerned about falling vaccination rates among America’s children after the COVID-19 pandemic fueled vaccine skepticism, particularly in red states. Trump has promised to cut off federal funding to schools that require vaccines, further compounding those fears. Adding Kennedy to the mix risks further undermining public confidence in vaccines.

“The notion that RFK Jr. would have any say in who’s selected [to be part of Trump’s administration] is very worrisome to me and many of my colleagues in public health,” W. Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, told The Hill.

“Many of us are old enough to remember what happened before there was a polio vaccine or a measles vaccine…there were millions of children that were adversely impacted due to the lack of protection from these types of diseases,” said Lipkin.

Even if Kennedy is not appointed to a public health position himself, Lipkin worried he could guide the former president toward placing people in top public health roles that would support cutting vaccine research or changing how vaccines are distributed.

Murphy shares those fears, and believes Kennedy could influence Trump to appoint someone who would stop tracking dangerous diseases as well.

Several high-ranking public health positions are political appointments, including the secretary of Health and Human Services, the surgeon general, the director of the National Institutes of Health, and the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Republicans backed a bill making the CDC director a Senate-confirmed position starting in 2025, largely due to the agency’s controversial role in issuing divisive COVID-19 guidance. That could end up giving Democrats the ability to block Trump’s CDC pick if he returns to the White House.