Public health experts say Robert F. Kennedy Jr is exactly who they thought he was.

The Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary — who is also the nation’s most well-known vaccine skeptic — is remaking the agency in his image, casting doubt on the benefits of vaccines, and erecting new barriers that will make it harder for people who want shots to get them, like requiring new vaccines to be tested against placebos.

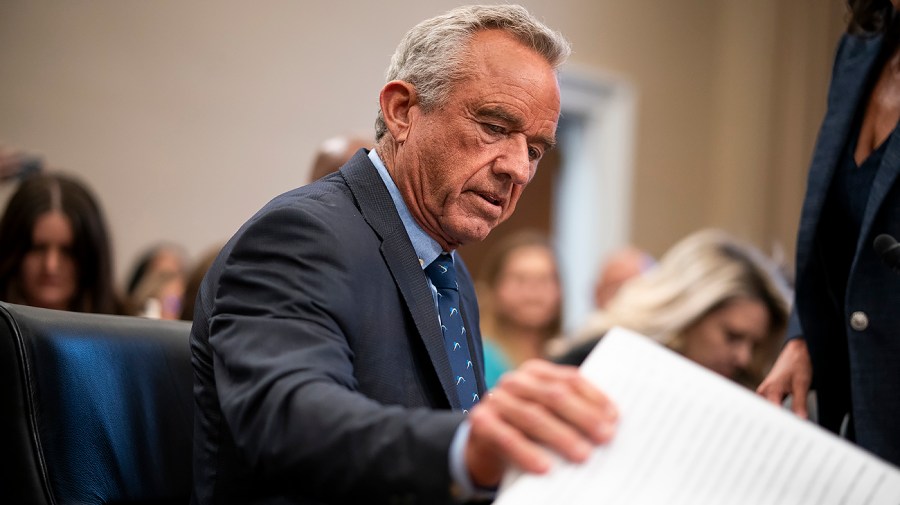

During his confirmation hearings and other recent congressional testimony, Kennedy sought to distance himself from the anti-vaccine movement.

He argued he is simply seeking good data about vaccine safety. He assured lawmakers he would not take away anyone’s vaccines and specifically pledged to Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) that he would not make any changes to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) vaccine advisory panel.

While testifying at a House Appropriations Committee hearing on May 14, Kennedy said his views on vaccines were “irrelevant.”

“I don’t want to seem like I’m being evasive, but I don’t think people should be taking medical advice from me,” he told lawmakers, after being asked whether he would vaccinate his own children today against measles.

Yet in the past week, Kennedy made an end run around the traditional process to change the recommendations about who should get a COVID-19 vaccine.

He threatened to bar government scientists from publishing in leading medical journals, and his office revoked hundreds of millions of dollars pledged to mRNA vaccine maker Moderna to develop, test and purchase shots for pandemic flu.

Kennedy has been critical of mRNA vaccines, and HHS said the funding was canceled because of concerns about the safety of “under-tested” mRNA technology.

Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, said the public should take Kennedy at his word.

“He’s right. We shouldn’t trust him,” Benjamin said. “He’s unbridled. He’s out of control, and so I am fearful that he will do more to undermine vaccine access and quality in the United States.”

Kennedy has a long history of opposition to vaccines. He petitioned the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021 to revoke the emergency use authorizations of the COVID-19 vaccines and threatened to sue the agency if it authorized COVID vaccines for children.

His latest moves to change the COVID vaccine recommendations on healthy children and pregnant women are raising serious concerns about the potential to pull back on even more vaccines.

“What I see is COVID has provided this natural starting point … to sort of have that opening salvo in a bigger, longer-term effort to reconstruct, undermine vaccine policy,” said Richard Hughes IV, an attorney at Epstein Becker Green and former vice president of public policy at Moderna.

The decision to change COVID vaccine policy was announced in a 58-second video clip shared on the social media site X.

“I couldn’t be more pleased to announce that as of today the COVID vaccine for healthy children and healthy pregnant women has been removed from the CDC-recommended immunization schedule,” Kennedy said.

Days after Kennedy’s pronouncement, the CDC issued new guidance that removed the recommendation for pregnant women to get a COVID shot but kept the vaccine on the childhood immunization schedule.

The agency changed the recommendation from its previous wording of “should” to say healthy children “may” get the COVID vaccine after consulting with a health provider, an apparent contradiction to Kennedy’s plan.

Despite the new wording, the changes buck the traditional method of making new vaccine recommendations.

The FDA decides whether to approve or authorize a vaccine, and the CDC’s independent vaccine advisory panel convenes in an open public meeting to decide questions like who should get it, when and how often. It then sends recommendations to the CDC director, who can endorse or reject the recommendations.

The director nearly always defers to the panel.

The HHS secretary isn’t typically involved in vaccine decisions, but there currently isn’t an acting CDC director.

“We’re seeing a total side-stepping of the nation’s leading public health agency,” said Richard Besser, a former acting director of the CDC and president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Besser said doctors rely on the recommendations of federal health experts, which are supposed to be based on the best available science and evidence. But doctors can’t be assured that’s the case anymore, he said.

Both Hughes and Benjamin said other changes to HHS vaccine policy are likely to be more nuanced and subtle than the agency’s actions on COVID.

“I would have said a couple months ago, obviously measles, obviously polio, those are childhood vaccines [that could be changed]. … But I think it’s going to be a little more subtle [than banning a shot]. It’s going to be a little more slow,” Hughes said.

In April, the CDC’s vaccine advisers met after a two-month delay to vote on recommendations for chikungunya vaccines, meningitis vaccines and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines.

About a month later, Kennedy personally signed off on recommendations for the chikungunya shot.

He has not acted on the other recommendations from the panel’s April meeting, including the use of a new meningitis vaccine and an expansion of RSV vaccines to high-risk adults ages 50-59.

The vaccine panel isn’t scheduled to vote on COVID vaccine recommendations until late June. Experts said it’ll be important to listen to what the panel members say, and whether they feel they have the freedom to discuss HHS’s recent actions.

“You’ve got a committee of advisers who were cut out of the loop. How are they going to handle that in a public forum?” Benjamin said.