Health

Unlocking the promise of CAR-T

Research across multiple fronts seeks to expand impact of a cancer therapy that has left patients and doctors awestruck

David Avigan doesn’t like to use the word “miracle” to describe CAR-T-cell therapy, but he knows what people mean when they do. He also remembers the first time it happened with one of his patients.

“As a field, we’re always a little cautious — our patients are on a roller coaster,” said Avigan, director of the Cancer Center at Beth Israel Deaconess and the Theodore W. and Evelyn G. Berenson Professor of Medicine for the Study of Oncology at Harvard Medical School. “But frankly, we’ve seen very dramatic responses in patients with advanced disease.”

First approved by the FDA in 2017, CAR-T-cell therapy enlists the body’s immune system in the fight against cancer. It has triggered rapid improvement in some of the sickest patients, those whose hopes had faded with the failure of one treatment after another. Physicians report astonishing results: tumors melting away over weeks or even just days and people who appeared to be on death’s door getting up and reclaiming their lives.

“They had received every other known therapy and experimental therapy — nothing worked — and after CAR-T therapy they would go into remission and just a week later, be walking around like they were totally normal, even if they got really sick during the therapy,” said Robbie Majzner, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Medical School and director of the Pediatric and Young Adult Cancer Cell Therapy Program at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. “We had one patient who almost died during the therapy and two weeks later he was leukemia-free and snowboarding. It was just unbelievable.”

Eric Smith, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical School and Dana-Farber’s director of translational research, immune effector cell therapies, describes CAR-T as a “platform” rather than a specific treatment. Its weapon is one of the body’s most potent fighters — the T-cell, refined over millions of years to destroy bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other invaders. The CAR, or chimeric antigen receptor, is the T-cell’s targeting system, which can be tuned by bioengineers to different targets. That tuning ability allowed Smith and others to engineer a therapy originally effective against leukemia and lymphoma into a weapon against a third blood cancer, multiple myeloma. It also underlies excitement around the therapy’s potential to treat not just other cancers but also noncancerous conditions such as autoimmune diseases and chronic infections.

“The platform is just so amenable to further engineering — the different things we can do to increase efficacy — that we’re very enthusiastic,” Smith said. “We’ll be curing a higher percentage of patients with the next iteration.”

Eric Smith said he’s seen many amazing recoveries. One of his first was the second patient ever to receive the CD-19 directed CAR-T-cell therapy, during his oncology fellowship at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

“We were shocked to see such an amazing clinical response,” Smith said. “We published a case report of a patient who had such rapidly progressive myeloma that in between starting on conditioning therapy and getting her CAR-T-cells, she developed paralysis from the myeloma in her spine. Then, with the CAR-T-cells, she was able to recover from that and do well for over a year. So yeah, that’s one of the things that does really make it different from other therapies.”

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

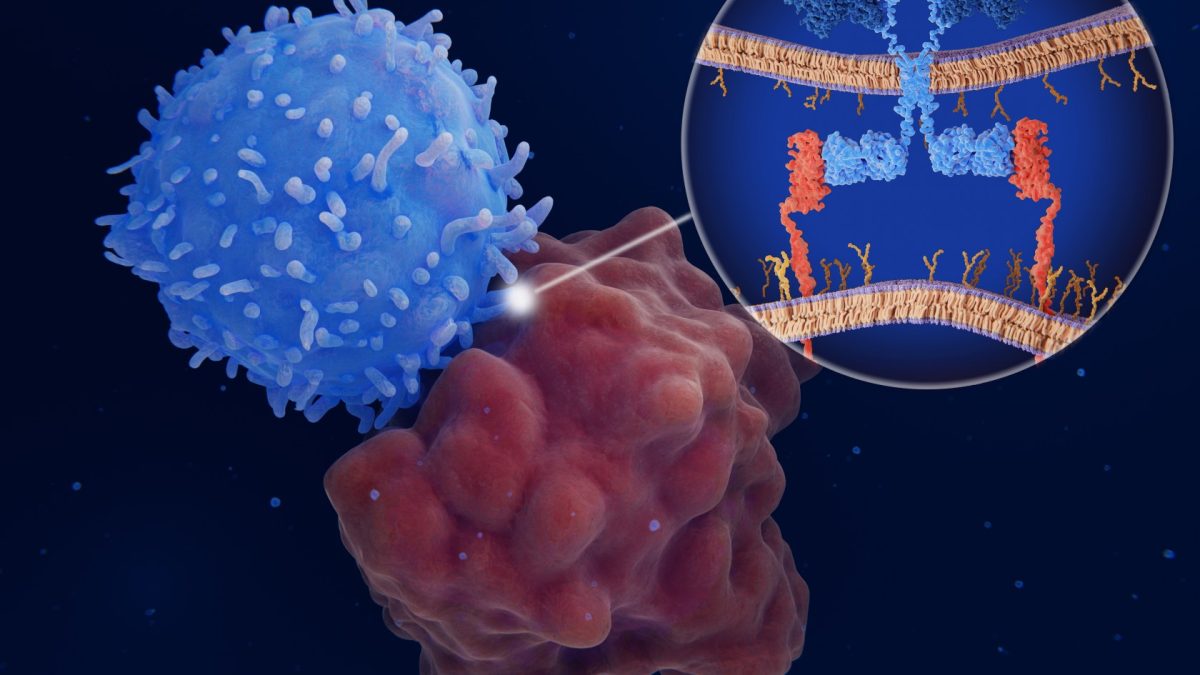

Prior to the development of CAR-T and other immunotherapies, cancer cells were protected from immune attack because they arise from the patient’s own tissues and aren’t recognized as an invader by the immune system.

In CAR-T therapy, physicians extract T-cells from the patient and send them to a cell manufacturing facility, where the CAR is added to the cell surface. The engineered cells are multiplied, frozen, and shipped back to the medical facility to be infused into the patient. Once in the body, the CAR attaches to a molecule — the antigen — on the cancer cell surface, signaling that the T-cell should attack.

How it works

T-cells are collected from a patient.

Source: Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; illustrations by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

T-cells are genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs.

CAR-T-cells are able to recognize and kill cancerous cells and help guard against recurrence.

The re-engineered cells are multiplied until there are millions of these attacker cells.

CAR-T-cells are infused back into the patient.

Inside the body, the CAR attaches to an antigen on the surface of a cancer cell.

The CAR signals the T-cell to release powerful cytotoxins, causing cell death.

The therapy has been most effective against leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma, which together accounted for 9 percent of U.S. cancer cases last year, affecting 187,000 Americans. Efforts to extend these gains to solid tumors are an important new frontier, specialists say, and a demonstration of the slow but steady momentum that characterizes scientific progress.

Among the most serious obstacles, along with the challenges presented by solid tumors, is the reality that CAR-T doesn’t work for everyone. Remission rates are currently between 50 and 90 percent, depending on the condition, and cancer is still the largest single cause of mortality for those undergoing the treatment.

“I wish I could say all cell therapy is curative for everybody,” said Marcela Maus, a professor at the Medical School and director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Program at Mass General. “We’re not there, but it has that potential and possibility for some patients. Cells are alive and they can have their own ‘thermostat’ for when they need to grow or when they need to shrink in response to something they sense in their environment. That really opens up the possibilities of regenerative medicine or single-shot cures that are very difficult to achieve with other modalities.”

Marcela Maus.

Kate Flock/Massachusetts General Hospital

One of Maus’ primary targets is the solid tumor problem, which is created in part by cell diversity, denser mass, and threats to the survival of CAR-T cells in the hostile immune environment around the malignancy. Last year, she teamed up with Harvard neurosurgeon Bryan Choi to test the therapy against glioblastoma, a devastating brain tumor that kills more than 90 percent of patients within five years. They tackled the diversity issue by engineering a two-pronged CAR that targeted two molecules typically found on the surface of different cancer cells, broadening the T-cells’ attack. The first three participants in the study saw dramatic improvements in their cancer, though the effects were durable in only one. Follow-up data on a total of 10 patients was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology this month.

Other research teams have reported mixed results in trials involving lung, prostate, ovarian, and gastric tumors.

“There’s been a lot of hope for the technology to be able to dramatically improve the lives of patients with other diseases for a long time,” said Maus. “That part is a little bit early and it’s been less straightforward to achieve.” Nonetheless, she’s seen enough to feel confident in “significant promise” for advances that bolster attacks against a wider range of cancers.

Another major concern with CAR-T are the side effects, whose severity — a 2024 study blamed side effects for almost 12 percent of non-cancer deaths among CAR-T patients — can cause some doctors to hesitate before recommending the treatment. One of the body’s responses to the therapy is to overreact, releasing proteins called cytokines that amplify the immune signal. Cytokine release syndrome can be severe, with nausea, vomiting, rapid heartbeat, and hallucinations among the symptoms. Another dangerous side effect is neurotoxicity syndrome, in which the heightened immune response affects the brain, causing temporary confusion in mild cases and coma in serious ones.

For patients who have exhausted other options, CAR-T-cell therapy, even with the side effects, is almost always worth trying, Avigan said. For those not so far along, the decision becomes murkier, but several studies suggest that CAR-T interventions offer advantages over standard therapy, he said. One powerful argument for earlier CAR-T is that repeated rounds of chemotherapy take a serious toll on the body, leaving late-stage patients with less effective T-cells. Moving CAR-T from a last resort to a second-line treatment has the potential to exploit T-cells that are more energetic and effective at clearing cancer from the body.

David Avigan, who’s treated hundreds of CAR-T-cell patients since the therapy first became available in 2017:

“There’s no question that for those of us who are in the middle of it, the transformative nature of this makes it an incredible privilege to take care of patients and help them in ways we couldn’t before. I’ve taken care of a lot of patients with CARs and have seen all parts of that spectrum.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“It’s not that this is a perfect therapy for every single person no matter what’s going on,” Avigan said. “But yes, you can take a step back and say, ‘Wow, we’re in a different place than we were 10 years ago.’”

Building blocks of a breakthrough

1987: Yoshikazu Kurosawa first describes the idea of modified CAR-T-cells that could target specific cancer cells.

1989-1993: First-generation CAR-T-cell therapies are designed by Zelig Eshhar and Gideon Gross, but the modified cells don’t survive long in the body and prove ineffective in clinical trials.

1998-2003: Michel Sadelain introduces a co-stimulatory molecule into CAR-T-cells, allowing them to remain active in the body. The team also modifies CAR-T-cells to target a protein on the surface of malignant cells in conditions like leukemia and lymphoma.

2011: Three adult patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia achieve complete or partial remission after receiving specific CAR-T-cell therapy.

2012: Six-year-old Emily Whitehead becomes the first pediatric patient to receive CAR-T-cell therapy. She recovered and is still thriving. AP photo

2017: First CAR-T-cell therapies are approved by the FDA. More are approved in the following years.

2024: Combining two strategies, CAR-T and bispecific antibodies called T-cell engaging antibody molecules, a Mass General Brigham group achieves dramatic regression in three glioblastoma patients. The work is particularly important because tumors can be more complicated to treat than blood cancers.

2025: A study finds that one-third of 97 patients with multiple myeloma, once considered incurable, remain alive and progression-free five years after CAR-T-cell treatment.

Over the next 10 years, CAR-T investigators hope to weaken or remove barriers to the therapy’s effectiveness as a cancer fighter — including cost — while also testing its potential against noncancerous conditions.

Mohammad Rashidian, a researcher and faculty member at Dana-Farber, has developed an “enhancer protein” designed to address two of CAR-T’s shortcomings: T-cell exhaustion that leads to a weak initial response, and responses that fade over time, as can happen in myeloma cases.

The enhancer protein, described in a study published a year ago, links the CAR to an immune system signaling molecule called IL-2. The molecule increases T-cell activity and promotes the development of memory CAR-T-cells, which have the potential to provide protection against cancer the way infection or vaccination might against infectious disease.

Mohammad Rashidian.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“I’m very optimistic,” Rashidian said. “The data that we have is really beyond what we had expected. You get better-quality T-cells and that translates to much better tumor clearance. If it replicates in patients, we would anticipate substantially better responses and hopefully a lot of patients should be cured.”

CAR-T’s potential extends to autoimmune diseases such as lupus, in which the immune system launches misdirected attacks on the body. For this version of the therapy, Maus said, the CAR is engineered to direct the CAR-T cell to attack B-cells, responsible for the autoimmune attack in lupus. The therapy seems to trigger a reboot of the immune system, she added, which curbs the B-cell attack in the months after treatment.

The cause of that reset is unknown, Maus said, but scientists are increasingly interested in wielding the therapy against other autoimmune conditions, including Type 1 diabetes. “There’s a whole group of autoimmune diseases where this could potentially have a really significant therapeutic benefit,” she said.

The benefits of CAR-T come at a hefty price, with a single cancer treatment costing upward of $400,000. Researchers are hopeful that refinements in care and drug development, among other advances, will act as a counterforce. Smith, of Dana-Farber, is particularly interested in the possibility of removing the cell manufacturing facility from the production cycle.

A key step in the bioengineering process is the vector’s delivery of the CAR’s gene to the T-cell. The cell uses those instructions to create the CAR on its surface before it’s infused back into the patient. Today, that step takes place in a facility, but Smith and others are working on a process that would inject the vector carrying the CAR gene directly into the patient. The vector would deliver the genetic instructions for the CAR to the T-cell while still in the body, triggering the T-cell to produce the appropriate CAR on the cell surface, all without a stop in a facility.

The idea still faces significant hurdles, including potential off-target effects should the vector deliver to cells other than T-cells, but Smith says it could be a game-changer, simplifying an arduous process for the patient and driving down costs.

Majzner, of Boston Children’s, is working in a landscape different from that of adult cancers, in part because drugmakers don’t want to limit themselves to medicines that treat only pediatric cases, which are significantly fewer. His answer is a CAR that targets a molecule found on cells in several cancer types. Called B7-H3, it would allow drugmakers to create CAR-T cells for pediatric patients with a range of cancers, increasing the patient population and possibly sparking more interest in development of therapies for pediatric patients.

Robbie Majzner, on how seeing impacts of CAR-T firsthand shifted his path:

“Before that, I always thought of lab research like rocket science, a bunch of pathways I didn’t want to memorize and far from the patient. Then, to have been working in Building 10 at the NIH where literally the therapy had been developed and then directly put into patients, you realize how close those things are. That really drove me to get involved in research. It wouldn’t have gone that way had I not seen those types of responses.”

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“We’ll have trials for that in solid tumors and in brain tumors,” Majzner said. “Perhaps it will leapfrog ahead for patients that now receive therapies for pediatric solid tumors that look like they did 40 years ago. Success would change the way we treat these cancers for sure.”

It would also further inspire specialists who have repeatedly come face to face with the power of CAR-T over the past several years. As Avigan put it: “There’s no question that for those of us who are in the middle of it, the transformative nature of this makes it an incredible privilege to take care of patients and help them in ways we couldn’t before.”

David Avigan doesn’t like to use the word “miracle” to describe CAR-T-cell therapy, but he knows what people mean when they do. He also remembers the first time it happened with one of his patients.

“As a field, we’re always a little cautious — our patients are on a roller coaster,” said Avigan, director of the Cancer Center at Beth Israel Deaconess and the Theodore W. and Evelyn G. Berenson Professor of Medicine for the Study of Oncology at Harvard Medical School. “But frankly, we’ve seen very dramatic responses in patients with advanced disease.”

First approved by the FDA in 2017, CAR-T-cell therapy enlists the body’s immune system in the fight against cancer. It has triggered rapid improvement in some of the sickest patients, those whose hopes had faded with the failure of one treatment after another. Physicians report astonishing results: tumors melting away over weeks or even just days and people who appeared to be on death’s door getting up and reclaiming their lives.

“They had received every other known therapy and experimental therapy — nothing worked — and after CAR-T therapy they would go into remission and just a week later, be walking around like they were totally normal, even if they got really sick during the therapy,” said Robbie Majzner, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Medical School and director of the Pediatric and Young Adult Cancer Cell Therapy Program at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. “We had one patient who almost died during the therapy and two weeks later he was leukemia-free and snowboarding. It was just unbelievable.”

Eric Smith, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical School and Dana-Farber’s director of translational research, immune effector cell therapies, describes CAR-T as a “platform” rather than a specific treatment. Its weapon is one of the body’s most potent fighters — the T-cell, refined over millions of years to destroy bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other invaders. The CAR, or chimeric antigen receptor, is the T-cell’s targeting system, which can be tuned by bioengineers to different targets. That tuning ability allowed Smith and others to engineer a therapy originally effective against leukemia and lymphoma into a weapon against a third blood cancer, multiple myeloma. It also underlies excitement around the therapy’s potential to treat not just other cancers but also noncancerous conditions such as autoimmune diseases and chronic infections.

“The platform is just so amenable to further engineering — the different things we can do to increase efficacy — that we’re very enthusiastic,” Smith said. “We’ll be curing a higher percentage of patients with the next iteration.”

Eric Smith said he’s seen many amazing recoveries. One of his first was the second patient ever to receive the CD-19 directed CAR-T-cell therapy, during his oncology fellowship at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

“We were shocked to see such an amazing clinical response,” Smith said. “We published a case report of a patient who had such rapidly progressive myeloma that in between starting on conditioning therapy and getting her CAR-T-cells, she developed paralysis from the myeloma in her spine. Then, with the CAR-T-cells, she was able to recover from that and do well for over a year. So yeah, that’s one of the things that does really make it different from other therapies.”

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Prior to the development of CAR-T and other immunotherapies, cancer cells were protected from immune attack because they arise from the patient’s own tissues and aren’t recognized as an invader by the immune system.

In CAR-T therapy, physicians extract T-cells from the patient and send them to a cell manufacturing facility, where the CAR is added to the cell surface. The engineered cells are multiplied, frozen, and shipped back to the medical facility to be infused into the patient. Once in the body, the CAR attaches to a molecule — the antigen — on the cancer cell surface, signaling that the T-cell should attack.

How it works

T-cells are collected from a patient.

Source: Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; illustrations by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

T-cells are genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs.

CAR-T-cells are able to recognize and kill cancerous cells and help guard against recurrence.

The re-engineered cells are multiplied until there are millions of these attacker cells.

CAR-T-cells are infused back into the patient.

Inside the body, the CAR attaches to an antigen on the surface of a cancer cell.

The CAR signals the T-cell to release powerful cytotoxins, causing cell death.

T-cells are collected from a patient.

Source: Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; illustrations by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

T-cells are genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs.

CAR-T-cells are able to recognize and kill cancerous cells and help guard against recurrence.

The re-engineered cells are multiplied until there are millions of these attacker cells.

CAR-T-cells are infused back into the patient.

Inside the body, the CAR attaches to an antigen on the surface of a cancer cell.

The CAR signals the T-cell to release powerful cytotoxins, causing cell death.

The therapy has been most effective against leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma, which together accounted for 9 percent of U.S. cancer cases last year, affecting 187,000 Americans. Efforts to extend these gains to solid tumors are an important new frontier, specialists say, and a demonstration of the slow but steady momentum that characterizes scientific progress.

Among the most serious obstacles, along with the challenges presented by solid tumors, is the reality that CAR-T doesn’t work for everyone. Remission rates are currently between 50 and 90 percent, depending on the condition, and cancer is still the largest single cause of mortality for those undergoing the treatment.

“I wish I could say all cell therapy is curative for everybody,” said Marcela Maus, a professor at the Medical School and director of the Cellular Immunotherapy Program at Mass General. “We’re not there, but it has that potential and possibility for some patients. Cells are alive and they can have their own ‘thermostat’ for when they need to grow or when they need to shrink in response to something they sense in their environment. That really opens up the possibilities of regenerative medicine or single-shot cures that are very difficult to achieve with other modalities.”

Marcela Maus.

Kate Flock/Massachusetts General Hospital

One of Maus’ primary targets is the solid tumor problem, which is created in part by cell diversity, denser mass, and threats to the survival of CAR-T cells in the hostile immune environment around the malignancy. Last year, she teamed up with Harvard neurosurgeon Bryan Choi to test the therapy against glioblastoma, a devastating brain tumor that kills more than 90 percent of patients within five years. They tackled the diversity issue by engineering a two-pronged CAR that targeted two molecules typically found on the surface of different cancer cells, broadening the T-cells’ attack. The first three participants in the study saw dramatic improvements in their cancer, though the effects were durable in only one. Follow-up data on a total of 10 patients was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology this month.

Other research teams have reported mixed results in trials involving lung, prostate, ovarian, and gastric tumors.

“There’s been a lot of hope for the technology to be able to dramatically improve the lives of patients with other diseases for a long time,” said Maus. “That part is a little bit early and it’s been less straightforward to achieve.” Nonetheless, she’s seen enough to feel confident in “significant promise” for advances that bolster attacks against a wider range of cancers.

Another major concern with CAR-T are the side effects, whose severity — a 2024 study blamed side effects for almost 12 percent of non-cancer deaths among CAR-T patients — can cause some doctors to hesitate before recommending the treatment. One of the body’s responses to the therapy is to overreact, releasing proteins called cytokines that amplify the immune signal. Cytokine release syndrome can be severe, with nausea, vomiting, rapid heartbeat, and hallucinations among the symptoms. Another dangerous side effect is neurotoxicity syndrome, in which the heightened immune response affects the brain, causing temporary confusion in mild cases and coma in serious ones.

For patients who have exhausted other options, CAR-T-cell therapy, even with the side effects, is almost always worth trying, Avigan said. For those not so far along, the decision becomes murkier, but several studies suggest that CAR-T interventions offer advantages over standard therapy, he said. One powerful argument for earlier CAR-T is that repeated rounds of chemotherapy take a serious toll on the body, leaving late-stage patients with less effective T-cells. Moving CAR-T from a last resort to a second-line treatment has the potential to exploit T-cells that are more energetic and effective at clearing cancer from the body.

David Avigan, who’s treated hundreds of CAR-T-cell patients since the therapy first became available in 2017:

“There’s no question that for those of us who are in the middle of it, the transformative nature of this makes it an incredible privilege to take care of patients and help them in ways we couldn’t before. I’ve taken care of a lot of patients with CARs and have seen all parts of that spectrum.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“It’s not that this is a perfect therapy for every single person no matter what’s going on,” Avigan said. “But yes, you can take a step back and say, ‘Wow, we’re in a different place than we were 10 years ago.’”

Building blocks of a breakthrough

1987: Yoshikazu Kurosawa first describes the idea of modified CAR-T-cells that could target specific cancer cells.

1989-1993: First-generation CAR-T-cell therapies are designed by Zelig Eshhar and Gideon Gross, but the modified cells don’t survive long in the body and prove ineffective in clinical trials.

1998-2003: Michel Sadelain introduces a co-stimulatory molecule into CAR-T-cells, allowing them to remain active in the body. The team also modifies CAR-T-cells to target a protein on the surface of malignant cells in conditions like leukemia and lymphoma.

2011: Three adult patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia achieve complete or partial remission after receiving specific CAR-T-cell therapy.

2012: Six-year-old Emily Whitehead becomes the first pediatric patient to receive CAR-T-cell therapy. She recovered and is still thriving. AP photo

2017: First CAR-T-cell therapies are approved by the FDA. More are approved in the following years.

2024: Combining two strategies, CAR-T and bispecific antibodies called T-cell engaging antibody molecules, a Mass General Brigham group achieves dramatic regression in three glioblastoma patients. The work is particularly important because tumors can be more complicated to treat than blood cancers.

2025: A study finds that one-third of 97 patients with multiple myeloma, once considered incurable, remain alive and progression-free five years after CAR-T-cell treatment.

Over the next 10 years, CAR-T investigators hope to weaken or remove barriers to the therapy’s effectiveness as a cancer fighter — including cost — while also testing its potential against noncancerous conditions.

Mohammad Rashidian, a researcher and faculty member at Dana-Farber, has developed an “enhancer protein” designed to address two of CAR-T’s shortcomings: T-cell exhaustion that leads to a weak initial response, and responses that fade over time, as can happen in myeloma cases.

The enhancer protein, described in a study published a year ago, links the CAR to an immune system signaling molecule called IL-2. The molecule increases T-cell activity and promotes the development of memory CAR-T-cells, which have the potential to provide protection against cancer the way infection or vaccination might against infectious disease.

Mohammad Rashidian.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“I’m very optimistic,” Rashidian said. “The data that we have is really beyond what we had expected. You get better-quality T-cells and that translates to much better tumor clearance. If it replicates in patients, we would anticipate substantially better responses and hopefully a lot of patients should be cured.”

CAR-T’s potential extends to autoimmune diseases such as lupus, in which the immune system launches misdirected attacks on the body. For this version of the therapy, Maus said, the CAR is engineered to direct the CAR-T cell to attack B-cells, responsible for the autoimmune attack in lupus. The therapy seems to trigger a reboot of the immune system, she added, which curbs the B-cell attack in the months after treatment.

The cause of that reset is unknown, Maus said, but scientists are increasingly interested in wielding the therapy against other autoimmune conditions, including Type 1 diabetes. “There’s a whole group of autoimmune diseases where this could potentially have a really significant therapeutic benefit,” she said.

The benefits of CAR-T come at a hefty price, with a single cancer treatment costing upward of $400,000. Researchers are hopeful that refinements in care and drug development, among other advances, will act as a counterforce. Smith, of Dana-Farber, is particularly interested in the possibility of removing the cell manufacturing facility from the production cycle.

A key step in the bioengineering process is the vector’s delivery of the CAR’s gene to the T-cell. The cell uses those instructions to create the CAR on its surface before it’s infused back into the patient. Today, that step takes place in a facility, but Smith and others are working on a process that would inject the vector carrying the CAR gene directly into the patient. The vector would deliver the genetic instructions for the CAR to the T-cell while still in the body, triggering the T-cell to produce the appropriate CAR on the cell surface, all without a stop in a facility.

The idea still faces significant hurdles, including potential off-target effects should the vector deliver to cells other than T-cells, but Smith says it could be a game-changer, simplifying an arduous process for the patient and driving down costs.

Majzner, of Boston Children’s, is working in a landscape different from that of adult cancers, in part because drugmakers don’t want to limit themselves to medicines that treat only pediatric cases, which are significantly fewer. His answer is a CAR that targets a molecule found on cells in several cancer types. Called B7-H3, it would allow drugmakers to create CAR-T cells for pediatric patients with a range of cancers, increasing the patient population and possibly sparking more interest in development of therapies for pediatric patients.

Robbie Majzner, on how seeing impacts of CAR-T firsthand shifted his path:

“Before that, I always thought of lab research like rocket science, a bunch of pathways I didn’t want to memorize and far from the patient. Then, to have been working in Building 10 at the NIH where literally the therapy had been developed and then directly put into patients, you realize how close those things are. That really drove me to get involved in research. It wouldn’t have gone that way had I not seen those types of responses.”

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“We’ll have trials for that in solid tumors and in brain tumors,” Majzner said. “Perhaps it will leapfrog ahead for patients that now receive therapies for pediatric solid tumors that look like they did 40 years ago. Success would change the way we treat these cancers for sure.”

It would also further inspire specialists who have repeatedly come face to face with the power of CAR-T over the past several years. As Avigan put it: “There’s no question that for those of us who are in the middle of it, the transformative nature of this makes it an incredible privilege to take care of patients and help them in ways we couldn’t before.”